| The Courier - N°158 - July - August 1996 Dossier Communication and the media - Country report Cape Verde source ref: ec158e.htm |

| ACP |

ACP

The economy of Cameroon: Better prospects but still a long way to go

It is an astonishing sight to behold during the rainy season. As you drive along the road from Yaoundé to Bamenda, you come to a point where human habitation starts - and it then continues unbroken for more than 100 kiLométres. Just before Bafoussam, and as far as the eye can see, every patch of land is cultivated. Bananas, oranges, mangoes, sugarcane, cassava, palm trees, groundnuts and maize grow luxuriantly in open fields and in the front and back gardens of many houses. This route, of course, takes you mainly through the western part of Cameroon, home to the Bamilelrés, recognised as one of the country's most enterprising and industrious ethnic groups. The population density here is 200 per km2 as opposed to 1 per km2 in the East.

The impact of this widespread farming, carried out by a large number of smallholders, is visible in the local markets, whether in Bafoussam, Mbouda or Bamenda. There, the stalls overflow with fruits and vegetables and prices are very low - a virtual paradise for the middlemen whose unmistakable presence is signalled by the significant number of trucks loading the produce for distribution throughout the country.

These scenes come as no surprise to the long-time observer of Cameroon's economy. The country achieved virtual self-sufficiency in food over 15 years ago. It is one of the few African countries to have been able to do this, thanks both to its physical endowments and an early recognition of its agricultural vocation.

Cameroon is often described as a microcosm of Africa, not just in terms of its make-up of English- and French speaking communities, but because it enjoys almost all the continent's climatic conditions. The south is equatorial, with two rainy seasons and two dry seasons of equal duration, the centre is Savannah country with one rainy season and one dry season, while the extreme north (part of the Sahel) is hot and dry. The country has a very good supply of rainfall - from 5000 mm annually in the southwest to around 600 mm near Lake Chad.

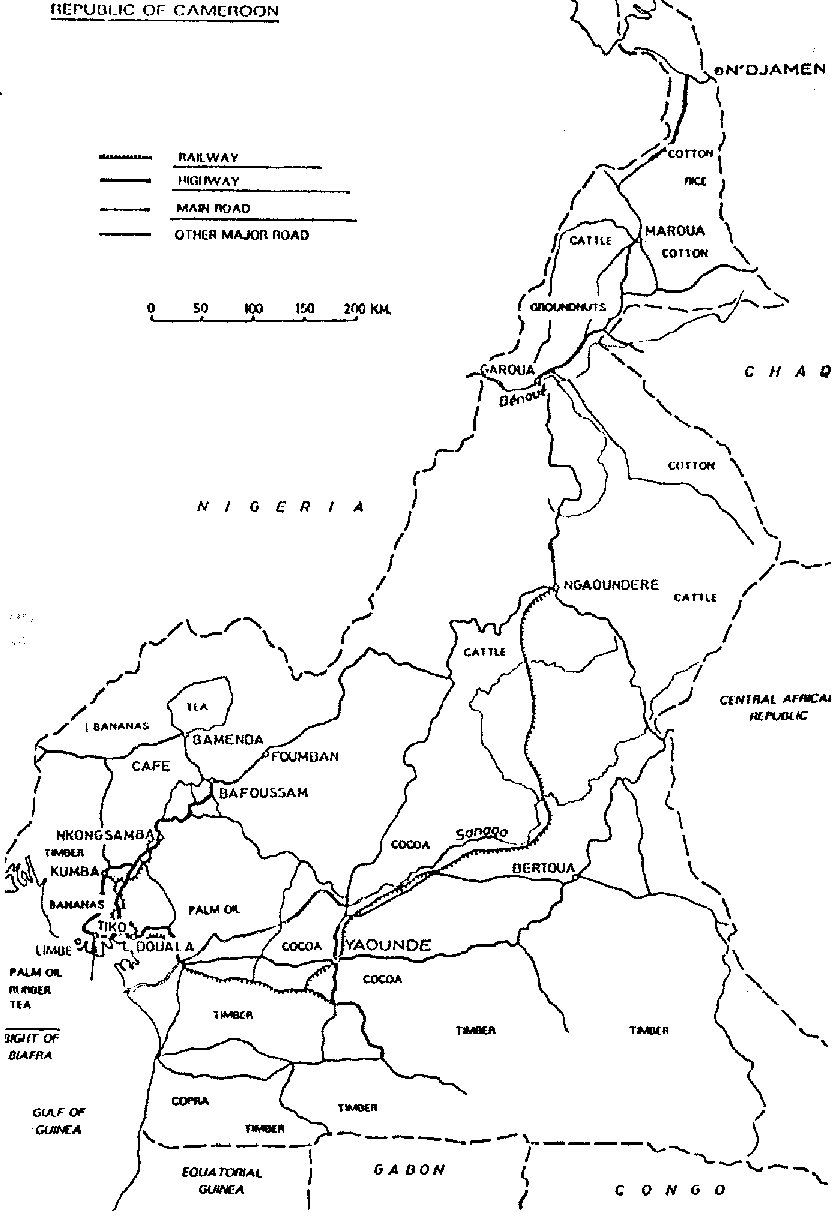

Such varied climates favour the cultivation of a variety of crops. Timber is produced mainly in the southern provinces while palm oil, tea, cocoa, coffee, rubber, timber and foodcrops are produced in the southwestern and western areas. The central and north provinces specialise in cattle and cotton production.

Concentration on agriculture

Cameroon has, not surprisingly, concentrated on agriculture. Indeed the government has given top priority to the sector in all its development plans since independence in 1960. It has been involved in the marketing of the main export crops and has provided subsidies to farmers in the form of low-priced fertilisers and pesticides for their cocoa, coffee, rubber, palm oil, etc. Almost three-quarters of the working population (the majority of whom are smallholders) are engaged in farming. And despite a low level of mechanisation, they are very efficient. The rate of growth in food outstrips the rate of population growth. Only a few largescale farmers or firms are involved in the production of cash crops.

Until the early 1980s, when oil came into the picture, these large scalefarmers and firms amounted for more than 70% of export earnings, 40% of state revenue and 32% of the Gross Domestic Product. The plan initially was to use oil revenues to further boost and transform agriculture. However, the dramatic increase in the country's oil production, combined with much higher world petroleum prices during the first half of the 1980s, made the sector not only Cameroon's biggest export earner, but also, in a certain sense, a 'spoiler' for agriculture. Increased revenues enabled the government to maintain the level of prices paid to farmers, even though world prices had slumped to disastrous levels. This created distortions in the market. (Later, when the oil price slumped, and revenues dropped sharply, producer prices were also reduced, bringing them closer into line with international prices.)

Agriculture's contribution to GDP declined steadily to around 21 % in 1985, rose to 27% in 1989 and has hovered around 30% ever since. The sector's share of export earnings has also fallen to about 40% of total exports by value.

Despite this, Cameroon's agriculture remains, comparatively, in a much better shape than that of most African countries. Indeed, it contributed in large measure to the country's reputation as one of Africa's economic successes in the 1980s. During that decade, growth averaged 8% per annum. However, the period was also marked by dramatic increases in oil revenues which induced significant policy changes as well as leading to maladministration. The government paid less attention to taxation and customs duties as sources of income and turned a virtual blind eye to smuggling which harmed the manufacturing sector. The civil service, on the other hand, expanded beyond reason, a phenomenon that some have attributed to patronage by the ruling single party.

Boom in public expenditure

Protected somewhat against fluctuations in earnings from export crops, by a strong but overvalued CFA franc, the government embarked on a wide range of capital expenditure and imports. Then, in 1987, international oil prices fell as dramatically as they had risen earlier in the decade. At the time, public spending was running at CFAF 8 billion - well above the CFAF 5.6bn the country actually earned. Revenues from oil continued their downward slide to CFAF4.5 bn in 1988, CFAF 2.8 bn in 1991 and CFAF 2.5 bn in 1994. 1995 saw a modest rise to CFAF 3 bn.

1987 thus marked the beginning of a rapid deterioration in Cameroon's financial situation. In the period which followed, civil servants' salaries were unpaid for months, several of the country's foreign missions were left without resources and both domestic and foreign debts worsened. In 1993, the government owed commercial banks around CFAF 3.3bn. Its external debt stood at around $7.5bn with a service ratio of more than 25% of foreign exchange earnings. The devaluation of the CFA franc in January 1994 improved the internal debt situation significantly. In February, the government signed a letter of intent with the IMF after agreeing to a series of reforms which included, among other things, rationalising the banking and insurance sectors, raising revenue from non-oil sources, bringing inflation down and reducing the budget deficit. In return the IMF provided a stand-by loan equivalent to CFAF 1.4bn. However, the agreement was suspended just a few months later when the Fund reached the conclusion that the government lacked the will to carry the reforms through. The 1994/95 budget foresaw a deficit of 4.5% of GDP - well above the IMF's guideline of 1.5%.

Meanwhile the country's financial situation had become so critical that it could no longer service its debts, most notably, those it owed to the World Bank. France, which had traditionally been ready to come to the rescue, refused to bail Cameroon out and it finally dawned on the authorities that structural adjustment was unavoidable. When, in September 1995, talks resumed with the IMF, the commitment to adjustment was no longer in doubt. The government agreed, in addition to fiscal reforms, to liberalise trade in cocoa, coffee and timber, to prune the civil service and to privatise state enterprises which dominate the industrial sector.

Commitment to reforms

Since then the reform process has been in full swing. The first and most important task has been to improve the government's financial position. The civil service, which employs more than 175000 people, is gradually being reduced and salaries have been cut. Trade is also being liberalised and subsidies are being removed. The 1995/96 budget, unveiled in June last year, was welcomed by the IMF. It included, for the first time in a long while, increases in income tax and a widening of tax bands. A series of measures have also been introduced to combat tax evasion and fraud. External signs of wealth, water and electricity consumption, and telephone bills are now being used as means of assessing income tax.

Responsibility for the collection of customs duties has been removed from the Customs Department which was often accused in the past of corruption and inefficiency. The task has been given instead to a Swiss-based preshipment inspection company.

The donor community has responded positively. With French assistance, the government has been able to clear its outstanding debt to the World Bank. The IMF has provided a stand-by credit facility of $101 million in support of the adjustment programme for 1995/ 96 and debts to the Paris Club covering the same period have been rescheduled. In addition, now that Cameroon has been reclassified as a poor country, it is entitled to benefit from the terms of the Naples Agreement, which allow for up to 67% of debts to western govemments to be written off. A number of creditor nations have either forgiven the country its debts or have reduced them substantially. More loans have come from France and a number of other donors, including the World Bank and the European Community.

The EC is financing a series of projects within the framework of the adjustment programme, including the restructuring of the civil service and preparation of the ground for privatisation.

Lately though, the donor community has been showing signs of disenchantment, following allegations of misuse of funds and perhaps even outright embezzlement. Last March, an IMF mission to Yaoundé failed to obtain an adequate explanation concerning the allocation of certain sums. The result, at the time The Courier went to press, was that an IMF loan for settlement of Cameroon's debt to the African Development Bank was being held up.

Dealing with the negative social impact

Figure

The sudden devaluation of the CFA franc in January 1994 halved Cameroon's purchasing power overnight. The government has since cut wages twice. The average salary of a top civil servant, which stood at around CFAF 300 000 before devaluation, is now less than CFAF 180 000 while the lowest paid government employees receive just CFAF 30 000. At the same time, prices, particularly of imported manufactured goods and inputs, have risen sharply. Increases of up to 150% have been recorded. By way of example, the price of a baguette (french bread), which was only CFAF 80 in January 1994 had risen to CFAF 130 by March 1996.

Although there is considerable hardship, Cameroonians are a great deal more fortunate than fellow Africans in many other countries undergoing a similar adjustment process. Staple food remains cheap and affordable to the vast majority, thanks to the continuing strength of agriculture. As a result, there are few, if any, cases of malnutrition.

A number of donors, including China, Belgium and the EC, are concentrating on health and education with the specific aim of reducing the negative social impact of adjustment. The EC, for example, has a project designed to strengthen health provision at the grassroots. This entails rehabilitating infrastructures (health centres and district hospitals in particular) and establishing medical supply centres in areas that are not covered by other donors. The project is governed by the principle of cost-recovery to ensure viability and sustainability. But one area where the donors cannot do much is in the field of job creation. There is growing unemployment and job prospects in the formal sector, at least in the short term, are not good.

In macro-economic terms, things are locking up slightly for Cameroon. After recording economic growth of 3% in 1994/95, the hope is for a 5% increase in 1995/96. However, Cameroon's main economic operators, grouped under the umbrella of GICAM (Groupement inter-patronal du Cameroun), expressed fears late last year that the country would not achieve this level of growth.

Cameroon exports a variety of primary commodities, most of whose prices have recovered in recent years, and devaluation has had a positive impact on the country's balance of trade. Specifically, it has helped make exports more competitive and in 1994/ 95 the trade surplus was a healthy CFAF 349bn, almost double the CFAF 128bn recorded in the previous year. There was a noticeable slowdown in the export of timber in the latter half of last year and the qualities of coffee and cocoa being sold were not up to the usual standard, a situation that led to both crops being shunned in the world market. Bananas exported to France were also meeting stiffer competition from French Caribbean bananas. However, the fact that rubber production has risen by more than 10%, while aluminium output and sales have increased, should help Cameroon to record another positive trade balance when the figures are next published.

The forestry sector, which has huge foreign-exchange earning and employment potential, is being rationalised as part of the current structural adjustment programme. The Canadian Agency for International Development

(CAID) has a five-year project to conserve and regenerate some 30 000 hectares. In fact, half of Cameroon is covered by forest and less than 500 000 ha is currently being exploited. The objective is to ensure that forest resources are exploited in the future at a sustainable level.

The private sector

Industry, which is still in its infancy, has been developed by the government since independence largely with a view to import-substitution, although with some gearing towards the regional market. It accounts for about 14% of GDP and is currently dominated by aluminium smelting. Although devaluation has lately improved the competitiveness of those enterprises that add value to locally available raw materials, the manufacturing sector as a whole faces two major challenges now that the government has accepted the idea that the economy is best driven by the private sector.

The first relates to private investments, which have been sluggish over the past ten years; a clear illustration of a lack of confidence in the economy. This was amply demonstrated when Cameroonians with funds abroad failed to repatriate them to take advantage of the CFAF devaluation as was widely expected. This phenomenon puts the whole privatisation exercise in jeopardy as it means that the government is more likely to have to rely on foreign entrepreneurs. The best the authorities can therefore expect in the short term, some observers say, is to convert those state enterprises that are not already joint-ventures into ones where private investors become the majority shareholders. Complete divestment will then take place gradually over a longer timescale. Overall, 150 state enterprises have been earmarked for sale.

According to André Siaka, director of Cameroon's Brewery, who is also Chairman of GICAM, another reason for the lack of investment was high interest rates. These hovered around 20% for many years. Even now, after the reform of the banking sector, interest rates remain very high and there are no borrowers, he told The Courier.

Donors again have been conscious of this and some of their interventions have reflected this concern. For example, Canada is providing funds for the establishment in Douala (the commercial capital) of a centre for the development of private enterprises. Meanwhile, the Chinese have promised to provide CFAF 7bn to enable a line of credit to be opened for small and medium sized enterprises.

The government itself is puting in place a number of incentives, according to Minister of Trade and Industry Eloundou Mani Pierre. The liberalisation of the economy and the reform of the customs regime in collaboration with UDEAC, to which Cameroon belongs, are part of these. Mr Mani told The Courier that with a population of under 12 million, Cameroun's most important market was Central Africa. He also, perhaps surprisingly, has high hopes for the new World Trade Aareement.

Cameroon meanwhile is reviewing its plan for the establishment of export processing zones with the help of its main donors.

It is also looking at other ways of attracting foreign investment, particularly in 'value-added' enterprises involved in the processing of locally available raw materials such as cotton, cocoa, coffee and timber.

Social and political peace

The second, and by far the more serious challenge facing manufacturing, is the problem of large-scale smuggling by petty traders.

Evidence of this abounds in the booming central market of Douala, where goods of all kinds can be found at very reasonable prices. Ironically the measures which were being taken and judged to be relatively effective against smuggling in recent years have had to be abandoned under structural adjustment rules imposed on the government.

As Mr Siaka pointed out, petty traders dealing in smuggled goods put pressure on enterprises, 'because they do not pay tax', and threaten to render domestic manufacturing uncompetitive. It is also widely acknowledged, however, that the small-scale traders, who dominate the informal sector, provide job opportunities to Cameroonians, which is important at a time of economic austerity. Indeed petty trading has arguably been the safety-valve, helping to ease the social pressures brought about by structural adjustment, and thus preventing civil unrest.

But the extent to which that safety-valve can withstand the emerging political pressures is a different matter. Democratisation, understandably, was one of the conditions imposed by donors for assistance to Cameroon. After a series of elections - presidential, legislative and municipal - which were marred by violence and deaths, there are still doubts about the health of democracy in the country. Indeed, there are signs that tension is mounting. And few would dispute that if Cameroon is to succeed economically, it needs both social peace and political stability.

Augustin Oyowe

Jacques Santer commends regional initiative

by Alex Kremer

Commission President's visit to West Africa

The European Union's commitment to regional development in sub-Saharan Africa is as strong as ever, but sustainable development can only come from Africa's own initiative. This was the message delivered by Jacques Santer, President of the European Commission, in his address to African heads of state at the UEMOA (Economic and Monetary Union of West Africa) summit in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, on May 10.

'I wish to emphasise from the start,' Mr Santer declared to the Presidents of Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'lvoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo, 'that the European Commission and the European Parliament are both determined to make our partnership even more dynamic and in tune with today's rapidly changing world.'

The presence of the Commission President at the UEMOA summit marks a milestone in the European Community's support for regional integration in the developing world. With its own Commission, Council of Ministers and Court of Justice, the UEMOA appears to be consciously following the supranational model of regional integration pioneered by the European Union.

The sequencing of UEMOA integration, however, is almost the reverse of the European model. Already linked by a single currency in the CFA franc, the West African Union's member states are now pressing ahead with plans for integration of their 'real' economies. The implementation timetable agreed in Ouagadougou covers freedom of establishment, free movement of capital, mutual macroeconomic monitoring and the first steps to customs union with the harmonisation of external tariffs and the lowering or removal of intra-regional barriers to trade.

President Santer indicated that the European Commission is keen to discuss how the European Development Fund (EDF) can support these initiatives. Such aid could take the form of technical assistance and training as well as direct budgetary support to mitigate the short-term costs of customs union.

UEMOA is not, however, an aid project. Its member states have designed it to stand on its own feet financially from the start. A 'community solidarity levy' was due to come into effect on 1 July 1996. The money will be used for a structural fund programme beginning in late 1997, as well as to finance the Union's operating costs.

Meeting with the President of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, Mr Santer said that it was particularly significant that his first official visit to Africa as President of the European

Commission was to Ouagadougou. Not only was it a reaffirmation of the partnership between Africa and the EU, and a statement of the EU's willingness to support regional integration in the developing world. It was also a tribute to the determination of the people of Burkina Faso and other African countries to promote their own development.

The European Community is Burkina Faso's second largest donor, contributing 10% of total aid payments in 1994. Since 1991, the EC has committed an average of ECU 45 million each year to development cooperation with this country, rising to a peak of ECU 100m in 1995.

Mr Santer visited the EDF-financed road improvement site at Tougan, close to the frontier with Mali, and noted that intra-regional transport links were an essential complement to the legislative programme of the UEMOA. He concluded his tour of regional cooperation projects with a visit to a photovoltaic pumping system financed by the EC under its West African solar energy programme.

Finally, on a more personal note, the Commission President was able to drop in on a project managed by the charity Chrétiens pour le Sahel. Mr Santer worked for this Luxembourg-based organisation before starting his career in politics and he was visibly pleased to see that it was still going strong - supporting home-grown African initiatives with a little financial help from the European Community.

A.K.

CTA - moving with the times

When the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) was inaugurated 11 years ago in Ede, Prince Claus of the Netherlands - whose interest in development issues is well-known - attestded as guest of honour. On 19 April, he returned to take part in the official opening of the CTA's new building in neigh bouring Wageningen in the Dutch province of Gelderland. The siting of the purpose built premises is significant. The town of Wageningen has long been an important European centre for agricultural research and the Dutch, of course, are renowned for their commitment to cooperation with developing countries.

The CTA may only have moved a short distance from its previous headquarters, but the Centre's 38-strong staff are also aware of the need to move with the times when it comes to fulfilling their role in the field of agricultural information. This point was particularly emphasised by CTA Director, Dr. R.D. Cooke in his presentation at the opening ceremony. Recalling the Centre's main tasks (see box) Dr Cooke spoke of the 'changing horizons and challenges' which they faced, and he focused on four specific aspects.

The first of these is the big change taking place in national agricultural systems, with the state withdrawing more and more in favour of the private sector and NGOs. This is being accompanied by a trend towards decentralisation with the result that the CTA has many more potential partners to cater for and work with.

Global liberalisation has also had an effect on the kind of information being sought by the CTA's 'customers'. In the past, demand was almost exclusively for scientific or technical information, notably aimed at increasing productivity. Dr Cooke reported that while this remained important, there was now an increasing interest in marketing and socio-economic aspects to facilitate decision-taking.

It came as no surprise to hear the Director highlight the challenge posed by new technologies such as electronic networking and digital storage. The key point here, he stressed, was to find ways of adapting these to ACP needs and realities. 'In the next century,' he argued, 'the haves and the heve-nots will be defined by their access to information.'

Finally, Dr Cooke referred to the growing significance of regional linkages. He indicated that the CTA was locking at ways in which it could help its partners to devise regional development programmes.

The declaration signalling the official opening of the building was made in the preceding presentation by E.F.C. Niehe who is Deputy DirectorGeneral for European Cooperation at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In his speech, Mr Niehe emphasised the relevance of the CTA, pointing out that while the world food situation had improved, 'we are now on the threshold of structural food insecurity'. He also spoke in more general terms about the future of ACP-EU cooperation and acknowledged that 'partnership, sovereignty and equality had been somewhat neglected' by donors. However, he suggested that these concepts were now 'coming back'.

From the ACP side, the Swaziland ambassador, CS. Mamba,who is co-President of the Committee of Ambassadors, took up the theme of food shortages in sub-Saharan Africa and identified some of the difficulties encountered by African producers, particularly in respect of new technologies and marketing. He also referred to the environmental challenges facing ACP countries, especially in the Caribbean and Pacific. He was keen, however, to stress that the picture was 'not entirely negative'. Thus, for example, new technologies and methods had had a positive impact on grain production in Zimbabwe, horticulture in Kenya, and cocoa and coffee in West Africa. Mr Mamba echoed Dr Cooke in stressing the advantages of regional markets, and concluded with a firm statement of support for continuing ACP-EU cooperation.

'History,' he said, 'will show that the Lomé Convention played a central role in the momentum of development.'

The final speaker was Steffen Smidt, Director-General for Development at the European Commission, who suggested that the CTA had played a pioneering role in developing a sectoral approach at a time when the focus of development cooperation tended to be on individual projects. 'The Centre', he said, 'has become a well-respected international institution in the field of agricultural information.' The Director General focused on the need for ACP countries to develop their own capacities and on the gap that exists 'between potential and reality', because of capacity limitations. The Centre, he believed, could 'help bridge this gap.' Mr Smidt also reiterated a point made earlier that the information flow should not just be in one direction. 'Information from South to North is vital,' he argued, to ensure better targeting of programmes in future.

After the speeches, guests had an opportunity to learn more about the CTA's work by speaking to the Centre's personnel and visiting a special exhibition illustrating the nature and purpose of the Centre's activities. _

Simon Homer About the CTA

The CIA's tasks are:

- to develop and provide services which improve access to information for agricultural and rural development ;

- to strengthen the Opacity of ACP countries to produce, acquire, exchange and utilise information in these areas.

Programmes are organised around three principal themes:

Strengthening information centres - designing strategies for improving agricultural information services; - promoting use of new information technologies; - providing training; - donating books.

Promoting contact and exchange of: experience among CTA's partners in rural development - seminars; - study visits.

Providing information on demand - publication s; - radio and audiovisual materials; - literature services for researchers; - Question and answer service.

(The address of the Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural cooperation can be found in the CTA section towards the end of the white pages in this issue.)

Bananas, Hamlet and the Windward IsIands

By Martin Dihm

What do the Windward Islands' banana industry and Hamlet have in common ? Both are intrigued by the same question: 'To be or not to be.' But unlike Hamlet, whose fete was decided rather quickly and tragically, the future of Windward Canibbean banana production is still open. And what is more, Windward producers have a distinct advantage over Hamlet. They can hire consultants to analyse their problem and come up with fresh solutions. That is what has happened. But before turning to the solutions, what have the problems been ?

The four Windward Islands; Dominica, St Lucia, St Vincent and Grenada, have long enjoyed preferential market access to the UK. This first permitted the creation of the industry and then secured its survival, even with production costs that are much higher than those of other producers.

A traumatic moment came when the European Community had to decide on a common market regime for bananas. Coming into effect in mid 1993 the regime maintained the principle of preferential access for traditional ACP producers. Nevertheless, it introduced a move towards greater market liberalisation. Fierce attacks on the regime by certain of the EU's trading partners have raised doubts about its viability. The system is due, in any case, to expire in 2002 when even further liberalisation seems likely.

All this could cause great difficulties for the Windward Islands which still depend substantially on banana exports to the EU. A decline in prices since mid-1993 and the appearance of new competitors in the previously protected UK market have further underlined the need for the Windwards to compete in a more liberal arena. The Islands commissioned a study, funded by the UK and the EC, into the competitiveness of their industry and on ways of improving its position. It was not the first study of this type, but earlier ones had had no real impact on the industry which had always been sufficiently protected to avoid swallowing the bitter pill of adjustment. This time, it was clear from the outset that action would have to be taken if the industry were to master the new situation.

The study provided a wealth of interesting insights and recommendations. The first big surprise - at least for outsiders - was the discovery that the industry was wasting considerable amounts each year through certain deficiencies in governance, management and production methods. The second theme of the study was the poor banana quality resulting from an inappropriate pricing system. In effect, price differences paid to farmers were not sufficient to reward extra attention to quality aspects.

The study's recommendations pertaining to management, production and quality were all agreed in a meeting on 29 September 1995, which brought together the Prime Ministers, the EC and other donors. Prime Minister Mitchell of St Vincent labelled this chance for the industry to get its business right as 'the last train to San Fernando'.

What has happened since then ? After some hesitation, the industry has indeed begun to 'take up arms against its sea of troubles' (to return to the Hamlet analogy). The EC, for its part, has taken the part of Horatio, the faithful friend. Its role is a delicate one though - for the EC has a lot of money available. Take, for example, the ECU 25m allocated to St Vincent in the 1994 STABEX exercise (roughly five times that country's national indicative programme). How are such funds to be injected reasonably into the islands without undermining their own strength and sense of purpose in pursuing the right strategy.

To answer this, one has to look at the actual requirements. Streamlining the banana industry is less a question of big infrastructure projects than of providing expertise to guide the necessary structural changes. It also means fewer people will be employed in the sector. Aid should, therefore, focus on technical assistance, promoting diversification, and social 'cushioning'.

The challenge, of course, remains considerable and the outcome will not be known for some time. But it is clear that the Windwards have taken bold steps in the right direction and that further steps are on the agenda. There is also little doubt that the islands small, sweet bananas can only be competitive in their market segment if they are produced and marketed professionally, and with dedication.

So what could Hamlet have learnt from this experience ? In short - get sound analysis and fresh advice from outside - and then boldly implement. And stick close to your good old friend, Horatio!

M.D.

British beef overshadows Development Council

The most recent meeting of the EC`s Development Council was one of the first to be hit by the non-cooperation policy adopted by the UK in protest at the export ban on British beef. The Overseas Development Minister, Linda Chalker, announced at the outset to her fellow ministers: 'I will not be able to agree today to the adoption of those texts... on which unanimity is required'. Britain is seeking agreement 'for a step-by-step lifting of the export ban', which was imposed after scientific evidence suggested a link between Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) - and its human 'equivalent', Creuzfeld Jakob Disease. Cases of BSE have been recorded across Europe, but the vast majority have been in the UK.

Texts which were approved included a regulation on refugees in non-Lomé developing countries. This makes available ECU 240 million over a four-year period (19961999) for longer term assistance to refugees and displaced persons - mainly in Asia and Latin America. Also agreed were two three-year programmes covering Aids control and environmental projects respectively. They will cover the period 1997-1999, and each has been allocated the sum of ECU 45m. In addition, ministers confirmed a regulation on the criteria for disbursing humanitarian aid.

But the British stance meant that a number of important resolutions were blocked, including a text on mounting projects which link emergency, rehabilitation and longer-term aid. Rino Serri, Italy's Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs who presided the Council meeting, said that once adopted, this approach would represent a 'qualitative leap for the EU's development policy.'

Other resolutions awaiting approval relate to the strengthening of coordination between Member States, evaluation of the environmental impact of development policies, decentralised cooperation, and migration and development. Since good headway was made on these subjects despite the British attitude, the texts are expected to be speedily agreed once the UK lifts its veto. Ministers also had an initial discussion on a paper presented by Commissioner Pinheiro on preventing conflicts in Africa.

As is customary at these biannual meetings, several delegations raised points of particular national concern. Belgium, for example, is worried about the Commission's proposal which would finally establish the single market in chocolate products while leaving Member States the choice of adapting their legislation to allow a vegetable oil content of up to 5% in chocolate. Belgium feels that this approach could ultimately prove harmful to cacoa-producing countries and claims that it will be difficult to control the exact percentage of oil used. Sweden, meanwhile, wants action to reform the UN institutions while Italy is keen to increase public awareness of development policies. Finland emphasised the need for better coordination between the European Community and its Member States on environmentally sustainable projects.

The Great Lakes region

There was backing for the June Round Table meeting on Rwanda organised by the UNDP, as well for the various diplomatic initiatives aimed at bringing stability to the Great Lakes region. On 27 May, the ministers dined with Emma Bonino, the European Commissioner responsible for humanitarian issues, and with former US President, Jimmy Carter, who has played a major role in the search to find a solution to the region's problems. Others active in this effort include South Africa's Archbishop Tutu, and former Presidents Nyerere and Touré of Tanzania and Mali respectively. Ministers also commended the efforts of the UN and the OAU.

Mr Serri said there was a 'desperate need for a ceasefire' in Burundi and called for a 'speeding up of the peace process and full deployment of available humanitarian and development aid.' He told journalists it was vital for the EU to make special efforts to strengthen the judicial systems in Rwanda and Burundi - 'so that the justice system can work properly and identify those responsible for the genocide.' He pledged that 'substantial resources' would be made available once peace is secured. Ministers also called for a control of arms sales to the region, although they have no power to legislate in this area, which remains the preserve of the Member States.

Outside the meeting place, Senegalese fishermen and NGOs joined forces to mount a protests against the effects of traditional EU fisheries agreements. These provide financial compensation to governments in exchange for access to their waters for EU vessels, but the protesters claim that they harm local fishing industries and disrupt food supplies. A significant number of agreements are due to come up for renewal later this year. NGOs are lobbying for a new and 'fairer' type of accord which provides for catch reductions, more selective fishing methods and the employment of locally-hired fishermen on EU boats. These proposals are all set out in a paper entitled 'The Fight for Fish: Towards Fair Fisheries Agreements,' published by Eurostep, a Brussels-based NGO.

D.P.